Quick Insights

- The Original Mohs Scale: Ten Key Minerals

- How to Actually Use the Mohs Hardness Scale (The Practical Part)

- Beyond the Top 10: The Mohs Scale for Everyday Life

- Why the Mohs Scale Still Matters in a High-Tech World

- Common Questions and Misconceptions About the Mohs Scale

- Taking it Further: Advanced Concepts Linked to Hardness

- Final Thoughts: A Tool for Your Toolkit

You've probably heard that diamond is the hardest natural material on Earth. But what does "hardest" actually mean? And how do we measure that? If you've ever tried to scratch a piece of glass with a quartz crystal or wondered why your wedding ring doesn't get scuffed up easily, you've already bumped into the practical world of the Mohs hardness scale.

Let's get straight to it. The Mohs scale is a simple, genius, and honestly, a bit old-fashioned way of ranking minerals based on their ability to scratch one another. It’s not about weight, or shine, or beauty. It’s purely about scratch resistance. Developed way back in 1812 by a German geologist named Friedrich Mohs, this scale has somehow stuck around for over 200 years. That’s longer than most scientific tools last. There’s a reason for that—it works, and it’s incredibly easy to use, even for a complete beginner.

I remember the first time I used it. I had a small collection of rocks as a kid, and I was frustrated that I couldn't tell them apart. A geology professor showed me the Mohs scale trick. We used a copper penny (hardness around 3) and a piece of glass (hardness 5.5). Suddenly, I could tell my calcite from my fluorite. It felt like a superpower. Simple, but effective.

The Core Idea: If Mineral A can scratch Mineral B, then Mineral A is higher on the Mohs scale than Mineral B. That’s the entire principle. No fancy machines needed (at least not for the basic test).

The Original Mohs Scale: Ten Key Minerals

Friedrich Mohs picked ten readily available minerals and arranged them in order of increasing hardness. He assigned Talc, the softest, as number 1, and Diamond, the hardest, as number 10. The brilliance of his system is its relativity. The difference in *actual* hardness between each number isn't equal. The jump from 9 (Corundum) to 10 (Diamond) is actually massive—diamond is about 4 times harder than corundum. But for a quick field test, that doesn't really matter.

Here’s the classic lineup, which you absolutely need to know if you're dealing with rocks or gems.

| Mohs Hardness | Mineral | Common Objects for Comparison | Simple Description |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Talc | Easily scratched by a fingernail | The softest. Feels greasy. Used in talcum powder. |

| 2 | Gypsum | Can be scratched by a fingernail with some effort | Your fingernail is about 2.5. Plaster of Paris is made from it. |

| 3 | Calcite | Scratched by a copper coin | A copper penny is ~3.5. Main component of limestone. |

| 4 | Fluorite | Easily scratched by a knife blade | Often colorful. A steel knife is around 5.5. |

| 5 | Apatite | Scratched with difficulty by a knife | The dividing line. Glass is usually 5.5. |

| 6 | Orthoclase Feldspar | Cannot be scratched by a knife; can scratch glass | A common rock-forming mineral. A good file is ~6.5. |

| 7 | Quartz | Easily scratches glass | One of the most common minerals. Sand is mostly quartz. |

| 8 | Topaz | Scratches quartz | A popular gemstone. Very hard and durable for jewelry. |

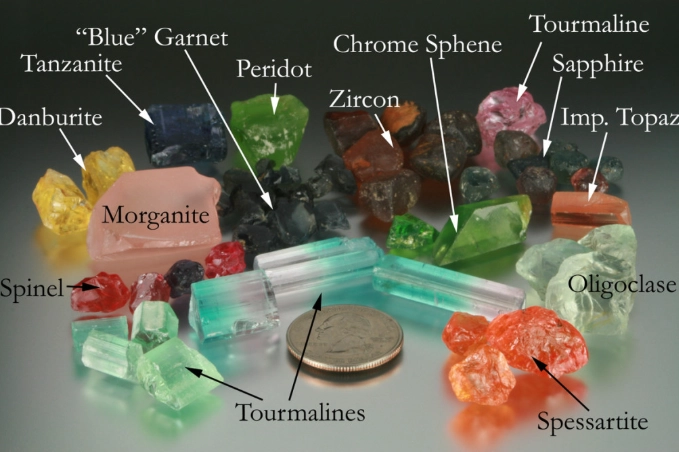

| 9 | Corundum | Scratches almost everything else | Includes ruby and sapphire. Used in industrial abrasives. |

| 10 | Diamond | Scratches all other materials | The ultimate benchmark. Used for cutting and grinding. |

So, if you have an unknown mineral and it can scratch glass but gets scratched by a piece of quartz, you know its hardness is between 5.5 and 7. Probably a 6, like feldspar. See how it works?

It’s a detective game for rocks.

How to Actually Use the Mohs Hardness Scale (The Practical Part)

Okay, theory is nice, but how do you do it? You don't need to carry ten minerals in your pocket. You use common objects as reference points. This is where the Mohs scale becomes genuinely useful for hobbyists, jewelers, and even contractors.

First, get a set of common "testers." Here’s what I keep in my field kit:

- Fingernail: Hardness about 2.5. If your mineral is softer, it’s a 1 or 2.

- Copper Penny (pre-1982 U.S.): Hardness about 3.5. A good test for calcite (3).

- Pocket Knife or Steel Nail: Hardness about 5.5. This is the big one. If the mineral scratches the knife, it’s above 5.5. If the knife scratches it, it’s below.

- Piece of Glass: A glass plate or the edge of a glass bottle. Hardness 5.5. Same logic as the knife.

- Porcelain Tile (unglazed underside): Hardness around 7. Good for testing if something is quartz (7) or softer.

- Quartz Crystal: Hardness 7. The final common tester. If your mineral scratches quartz, it’s an 8 or above.

The trick is to start with an object you think is softer than your mineral. Try to scratch the *mineral* with the object. If it leaves a mark, the object is harder. Then try scratching the *object* with the mineral. If the mineral leaves a mark on the object, the mineral is harder. You need a fresh, clean surface for a good test, not a weathered one.

Pro Tip: A "scratch" is a permanent, powdered line. A "mark" that wipes off is just a streak of the softer material and doesn't count. Press firmly and drag. Don't just tap.

Wait, Is the Mohs Scale Flawed?

Let's be honest here. The Mohs hardness scale isn't perfect. Far from it. Scientists in labs use more precise scales like the Vickers or Knoop hardness tests, which measure the exact force needed to make an indent. The Mohs scale is qualitative, not quantitative. It tells you order, not exact values.

Another issue? It only measures one type of hardness: scratch hardness. There's also toughness (resistance to breaking) and cleavage (how it splits). A diamond (10) can be shattered with a hammer, while a piece of jade (hardness 6-7) is famously tough and resistant to breaking. So, a high Mohs number doesn't mean indestructible. This is a huge point of confusion.

Also, the scale gets a bit fuzzy for materials that aren't pure minerals. What about steel, plastic, or your smartphone screen? We’ve extended the concept, but it’s not what Mohs originally intended.

Beyond the Top 10: The Mohs Scale for Everyday Life

This is where it gets fun. You can mentally apply the Mohs scale to almost anything.

Your Kitchen: A good kitchen knife blade is about 5.5-6.5. Your ceramic plate? The glaze is around 6-7. That’s why metal knives don’t scratch most plates. But drop a piece of quartz gravel on it, and you might get a chip.

Your Floors: Why is some flooring more scratch-resistant? Engineered quartz countertops are full of, well, quartz (hardness 7). They resist scratches from cutlery (5.5) beautifully. Softer marble (calcite, hardness 3) etches easily from lemon juice and gets scratched by everything harder than a copper penny.

Your Car: Clear coat paint is designed to be hard, often in the 7-9 range, to resist fine scratches from dust (which often contains quartz).

Here’s a quick ranking of some common non-mineral items, which is super useful:

- Lead of a pencil: 1 (it's graphite, close to talc!)

- Chalk: 2-3

- Plastic from a bottle: 2-3

- Standard Aluminum: 2.5-3

- Gold (pure 24k): 2.5-3 (That's why wedding rings are alloys!)

- Copper: 3

- Brass: 3-4

- Iron/ Low-Carbon Steel: 4-4.5

- Hardened Steel (file, knife): 5.5-6.5

- Window Glass: 5.5

- Porcelain: 7-8

- Tungsten Carbide ("tungsten" wedding bands): 8.5-9

- Silicon Carbide (sandpaper grit): 9-9.5

- Boron Nitride ("white graphite"): 9.5

See? Suddenly, the world makes more sense. You understand why a steel key can scratch your plastic phone case but not your glass screen protector.

Why the Mohs Scale Still Matters in a High-Tech World

With all our advanced technology, why hasn't this 19th-century tool been retired? Simple: accessibility and cost. An industrial Vickers hardness tester costs thousands of dollars and requires a trained operator and a polished sample. A Mohs test requires a pocket knife and a piece of glass. For field geologists, rockhounds, and jewelers making a quick assessment, it’s unbeatable.

Its primary modern uses are in a few key areas:

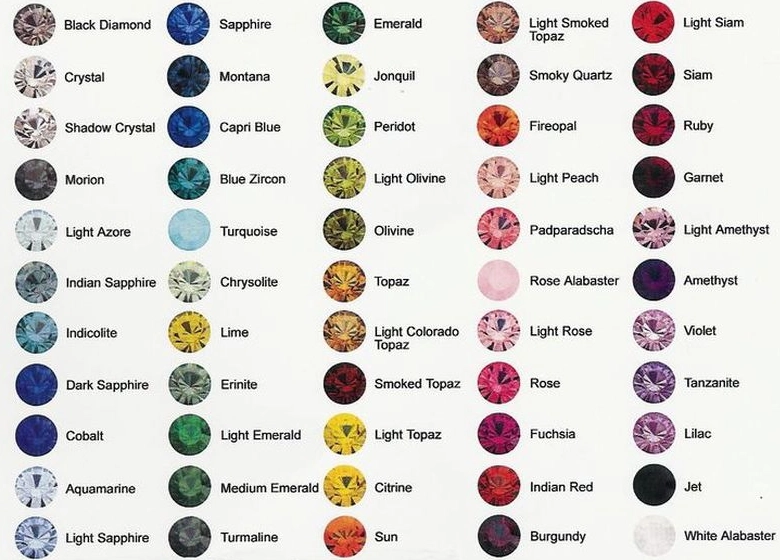

- Gemology and Jewelry: This is the big one. The Mohs scale is crucial for gemstone durability. A gemstone's hardness determines how well it will survive daily wear. Stones below 7 (like opal, turquoise, pearl) are considered delicate for rings, as they can be scratched by common dust (quartz). Stones 8 and above (topaz, corundum, diamond) are excellent for everyday rings. The Gemological Institute of America (GIA), the world's foremost authority on gems, heavily references the Mohs scale in its durability guidelines.

- Geology and Mineral Identification: It’s a first-pass test. Combined with streak, color, and cleavage, it’s a powerful identification tool. Textbooks and field guides are built around it.

- Industrial Abrasives and Tooling: Industry uses extended, more precise versions of the hardness concept, but the principle is the same. You need an abrasive that's harder than the material you're cutting or polishing. Diamond-tipped blades cut concrete because diamond (10) is harder than the quartz (7) in the concrete.

- Material Science and Engineering: When developing new ceramics, coatings, or composites, scratch resistance is a key property. The Mohs scale provides a simple conceptual framework.

The Bottom Line: The Mohs scale isn't the most precise tool in the shed, but it's the most reliable, dirt-cheap, and universally understood one. It bridges the gap between professional science and public understanding.

Common Questions and Misconceptions About the Mohs Scale

Let’s clear up some confusion. I hear these questions all the time.

Taking it Further: Advanced Concepts Linked to Hardness

If you really want to geek out, the story of hardness goes deeper. The reason one material scratches another comes down to atomic bonds and crystal structure. Diamond is hard because every carbon atom is strongly bonded to four others in a rigid tetrahedral network. Talc is soft because its atoms are arranged in sheets that slide over each other easily.

For professional applications, the Mohs scale is often supplemented or replaced by absolute hardness scales. These measure the actual pressure required to create an indentation. If you look up a comparison chart, you’ll see the exponential jump on an absolute scale. Talc might be 1, Gypsum 3, Calcite 9, Quartz 100, Corundum 400, and Diamond 1600. This shows why the gap from 9 to 10 is so colossal.

If you're working on a serious project requiring precise hardness data, you should consult resources like the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) or materials databases, which provide these quantitative values.

From a pocket knife in a field to atomic bonds in a lab—that’s the journey of understanding hardness.

Final Thoughts: A Tool for Your Toolkit

The Mohs hardness scale is a testament to the power of a simple, elegant idea. It’s not the final word on hardness, but it’s almost always the first word. Whether you’re identifying a mystery rock in your backyard, choosing a durable gemstone for a pendant, or just trying to figure out why your new countertop is holding up so well, this 200-year-old scale has your back.

Grab a steel nail and a piece of glass. Find a pebble. Give it a try. You might be surprised at what you discover. It turns the world from a collection of random hard stuff into an ordered, understandable system. And in science, that’s half the battle.

Just remember its limits. Hardness isn’t toughness. A high number on the Mohs scale doesn’t make something bulletproof. But for answering the simple question—“Can this scratch that?”—there’s still nothing better.