Ask a room of gemologists "What's the rarest gem?" and you'll get a heated debate, not a consensus. Most articles will lazily point to Painite and call it a day. But that's surface-level. The real answer depends on how you define "rare." Is it the gem with the fewest known faceted stones? The one from a single, depleted mine? The mineral that exists but is almost never gem quality?

After years in this field, I've seen collectors chase myths. The true #1 isn't just rare; it's virtually a ghost in the trade. It's the gem you can't buy, even with a blank check. We're going past the usual listicles to find it.

What You'll Discover

The Usual Suspects: Red Diamonds, Painite & More

Let's clear the table. When people think "rarest," these names come up.

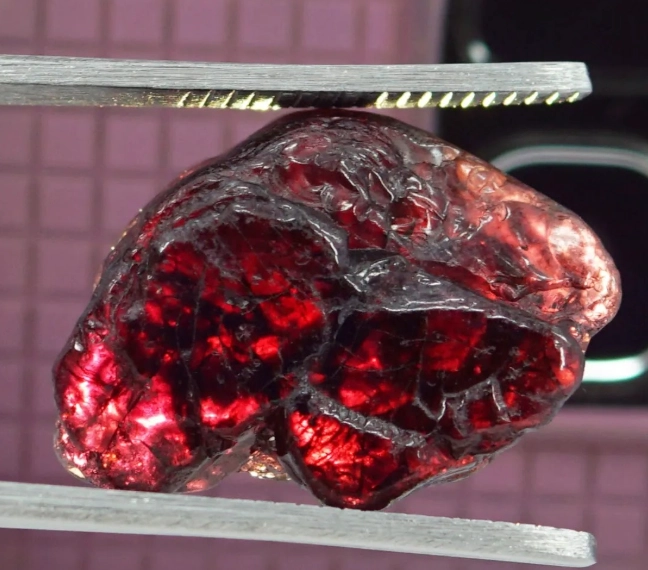

Red Diamonds: The poster child for rarity and price. The Moussaieff Red (5.11 carats) and the Hancock Red (0.95 carats) are legends. Their color comes from a rare plastic deformation in the crystal lattice. Argyle mine in Australia was the primary source, and it's now closed. Maybe a handful of true reds over 0.5 carats appear per decade at auction.

But here's the twist: they do appear. They are traded. You can find their prices in public records. This makes them incredibly rare, but not unobtainable in the strictest sense for the ultra-wealthy.

Painite: For 50 years, Painite held the Guinness World Record as the world's rarest mineral. Discovered in Myanmar in the 1950s, only two crystals were known for decades. New finds in Myanmar in the 2000s changed that. Today, several thousand crystals are known, and you can actually buy small, often included, faceted Painite stones from specialist dealers. Its rarity plummeted from "mythical" to "extremely rare but available." A classic case of how a new deposit can rewrite the rules.

Serendibite, Jeremejevite, Grandidierite: These are the darlings of mineral collectors. Faceted gems are museum pieces. A clean, well-cut serendibite over two carats is a unicorn. But again, a handful of dealers in Tokyo or New York might have a tiny specimen. They exist in the commercial sphere, albeit in a whisper.

What Makes a Gem "The Rarest"? A 4-Point Test

This is where most articles stop. They list gems and pick one. But a true expert applies a filter. To be the #1, a gem must score catastrophically high on all four points of this rarity matrix.

1. Geological Scarcity: One, maybe two, micro-deposits on the entire planet. The original mine is often a single pocket in a hillside, long gone.

2. Crystal Habit & Quality: The mineral forms tiny, splintery, or massively included crystals. Faceting a clean, well-proportioned gem from it is like carving a statue from a cracker.

3. Market Availability: The number of faceted stones known could fit in a shot glass. They are almost exclusively in institutional collections (Smithsonian, British Museum). Zero presence at Tucson gem shows or online dealer catalogs.

4. Gemological Desire: It must be something people actually want as a gem—colorful, sufficiently hard, with appealing optics. A rare brown mineral nobody wants to wear doesn't count.

Apply this test, and the field narrows dramatically.

The Verdict: The Actual #1 Rarest Gem

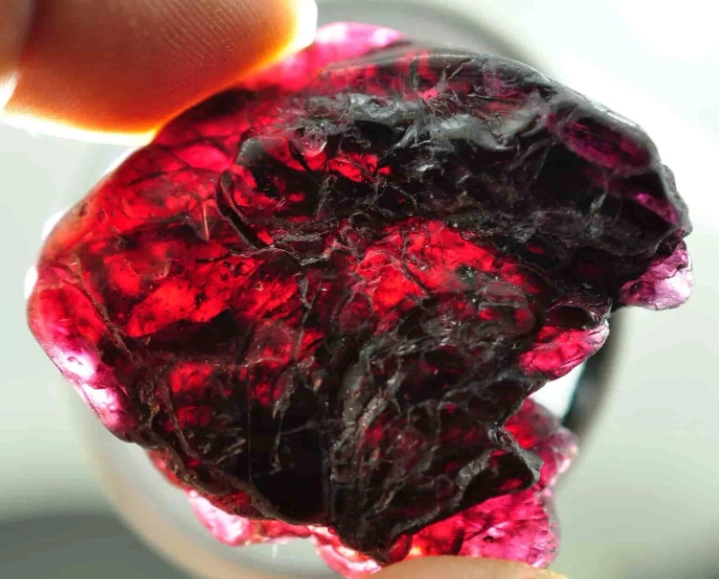

Based on the strictest application of the matrix—particularly Market Availability—the title goes to a specific variety of a gem often confused with Painite: Blue Painite, also known as Type II Painite, which is actually the mineral Grandidierite from a specific locale.

Let me explain this mess, because nomenclature is half the battle. In the early 2000s, a blue-green mineral was found in Myanmar and mistakenly identified as a new type of Painite ("Type II"). It was later correctly identified as Grandidierite. But the gemological world had already dubbed it "Blue Painite." This specific material, from that one Myanmar occurrence, is the subject of our discussion.

Why is it the #1?

- The Source: A single, incredibly limited pocket in the Mogok region. It was mined out almost immediately.

- The Yield: Of the rough recovered, an infinitesimal amount was clean enough to facet. We're talking grams of facetable material from the entire find.

- The Numbers: Reputable experts like Gems & Jewellery magazine have reported that there are fewer than ten faceted stones of this material known to exist in private hands. Most are under 0.5 carats.

- The Market: You will not find it for sale. Full stop. Not at auction, not with the most connected dealers. The known stones are locked away in collections or museums. A 2023 report from a Myanmar gemologist suggested a tiny, new pocket was found, but the material was mostly opaque. The hope for new facetable supply remains near zero.

A red diamond is a superstar you might glimpse at a gala auction. This "Blue Painite"/Grandidierite is a ghost. It wins on the pure, brutal metric of unobtainability.

The Runner-Up: A Case Study in Changing Rarity

If you need a "name" that's easier to grasp, classic Grandidierite from Madagascar (the green-blue kind) is a strong contender. But here's the nuance: small, included pieces have trickled into the market in the last 15 years. A dedicated collector with deep pockets can find a specimen. It's moved from the "ghost" category to the "extremely rare" category. This shift is crucial—it shows rarity isn't static. A new find can demote a champion.

Why Rarity Doesn't Always Mean Value (And Vice Versa)

This is the biggest misconception. Rarity is just one leg of the value stool. The others are beauty (demand) and durability.

You can have an incredibly rare gem that's not valuable because it's ugly or crumbles to dust. Conversely, a fine Kashmir sapphire is not the rarest gem in the world, but its combination of supreme beauty, historical prestige, and genuine rarity makes it one of the most valuable per carat.

The "Blue Painite" I described is priceless to a museum curator but might not command a record price at auction because its beauty is niche (a subtle blue-green) and its fame is limited to a small circle of specialists. A 5-carat red diamond is objectively less rare from a "number of stones" perspective, but its fiery red beauty and diamond durability create insane demand among billionaires, hence the $2+ million per carat prices.

When investing, don't just chase the rarest. Chase the rarest that is also beautiful, durable, and desired.

Your Rare Gem Questions Answered

This is a trick of definitions. The mineral Painite was rarer for decades. Today, facetable Painite is arguably more commercially available than a red diamond. However, the specific "Blue Painite" (Myanmar Grandidierite) variant is considered rarer than both because of its near-zero market presence. Red diamonds have a market price and auction history; they are traded assets. The top-tier rare gems often don't even have a market.

For the true #1 contenders, think natural history museums, not jewelry stores. The Smithsonian and the British Natural History Museum are your best bets. You'll be looking at a small, labeled specimen in a glass case, often uncut. It won't be glamorous, but it's real. For the famous "rare" gems like large red diamonds or Paraíba tourmalines, follow major auction houses (Sotheby's, Christie's) for their preview exhibitions in New York, Hong Kong, or Geneva.

There's no official board. Ranking comes from consensus among academic mineralogists (who track mineral species) and high-end gem dealers (who track facetable material). Institutions like the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) publish research on specific stone localities and yields, which becomes the reference. The ranking emerges from shared knowledge of mine outputs, the number of documented facetable stones, and decades of trade experience. It's more folklore and collective memory than a spreadsheet, which is why definitions can be fuzzy.

Forget the ghosts. Look for documented rarity with stable demand. A spinel from the historic Kuh-i-Lal deposit in Tajikistan (a single source). A sapphire from the extinct Kashmir mine with undoubtable provenance. An unheated ruby from Myanmar's Mogok Valley over 3 carats. These have established markets, recognizable beauty, and verifiable scarcity. The key is independent lab reports (GIA, Gubelin, SSEF) that confirm origin and lack of treatment. The premium is for proven, desirable rarity, not just a obscure mineral name.

The hunt for the rarest is fun, but it's a moving target. Today's champion could be dethroned by a backhoe in a remote valley tomorrow. The real lesson isn't about finding a single name; it's about understanding the fragile, wondrous geology that creates these treasures in the first place. That's a story that never gets old.