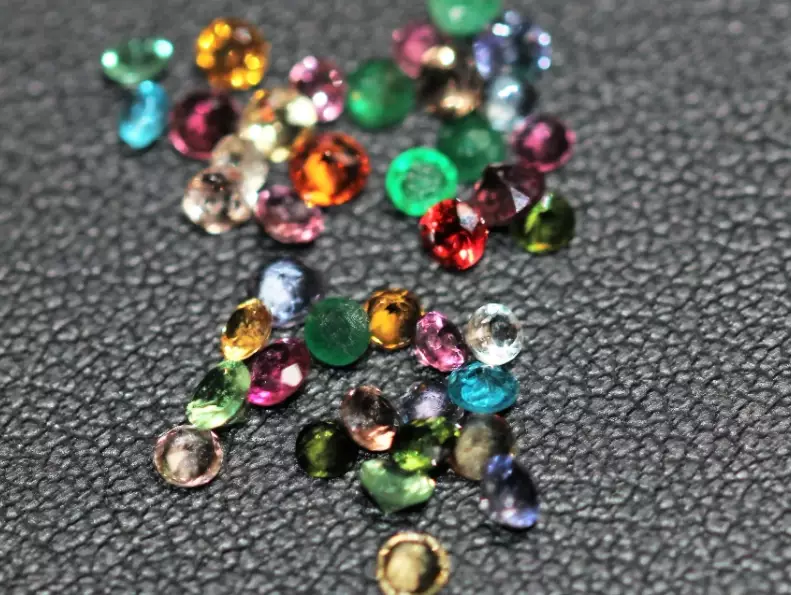

Walk into any jewelry store today, and you'll see lab-grown diamonds and sapphires sitting right next to their natural counterparts. The technology is incredible. It's also made a lot of people wonder: can we make *everything* in a lab now? Is there any gemstone left that's truly, exclusively a product of nature?

The short answer is yes. While labs can replicate the chemistry of most gems, a handful remain stubbornly, fascinatingly resistant to commercial synthesis. It's not always about impossibility, but often about a brutal combination of impossible complexity and zero economic sense. I've spent years in this trade, and the confusion I see isn't about diamonds—it's about the quieter, more complex stones where the line between natural and synthetic gets gloriously muddy.

Your Quick Guide to the Unmakable Gems

The Unbreakable Code: Why Some Gems Resist the Lab

Think of creating a gem in a lab like trying to bake the world's most complex cake in a microwave. You might get the basic ingredients right, but the texture, the subtle flavor layers from slow baking, the specific crunch from a unique oven—that's the hard part.

For gems, three main locks keep the lab door shut.

The Pressure Cooker Problem

Some gems, like high-quality jadeite jade, form under insane pressures deep in the earth's crust over millions of years. We're talking about forces that would crumple a submarine. Replicating that sustained, ultra-high-pressure environment in a lab isn't just hard; it's wildly expensive. The energy cost alone makes producing commercial quantities a financial fantasy. You could spend $100,000 to create a $500 piece of low-grade synthetic jade. Nobody's doing that.

The Biological Signature

This is the big one for organic gems. A natural pearl is the result of a biological defense mechanism in a living mollusk. It's not just calcium carbonate; it's layers of nacre secreted in response to an irritant, with a unique microstructure and often subtle color hues from the animal's environment. Labs can make beautiful beads and coat them, but creating the exact, complex structure of a natural pearl from the inside out? That's bio-engineering, not gem synthesis. Same goes for amber—fossilized tree resin. Its beauty and value are tied to its age, its inclusions (like ancient insects), and its specific chemical polymerization over millennia. You can make plastic that looks like it, but it's not amber.

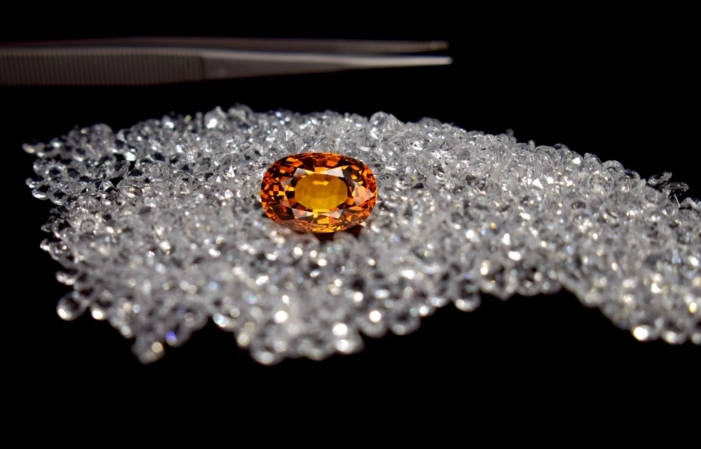

The "Why Bother?" Economic Wall

This is the quiet reason that doesn't get enough airtime. Let's take a gem like alexandrite that can change color. Yes, synthetic alexandrite exists. But the natural version is so spectacularly rare and valuable that the synthetic market is tiny and specialized (mostly for lasers). For many other rare collector stones, the market is small and knowledgeable. The cost of developing and scaling up synthesis for these niche gems far outweighs any potential profit. The lab-grown diamond business works because the natural diamond market is massive. For rare gems, there's no economic engine to drive the research.

A quick reality check: When someone says a gem "cannot" be lab-grown, they usually mean it cannot be profitably and convincingly grown for the commercial jewelry market. Scientific papers might report microscopic crystals created under extreme conditions, but that's a world away from a cuttable, sellable gemstone.

The "Unmakable" List: Gemstones That Defy Synthesis

Based on the locks described above, here are the champions of natural persistence. This isn't just a list; it's a look at where nature still holds the crown.

| Gemstone | Primary Reason for Resistance | The Market Reality | Common Confusions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Jadeite Jade (Imperial Green) | Extreme pressure & specific sodium-rich chemistry required. Formation process is too complex and slow to replicate economically. | High-end jadeite is one of the most expensive gems per carat. No commercial synthetic exists that fools an expert. | Often confused with nephrite (another jade) or dyed quartz. "Lab-created jade" typically refers to glass or composite simulants, not true synthetic jadeite. |

| Natural Pearls (Saltwater) | Biological origin. Requires a living mollusk's specific nacre-secreting process over years. | The vast majority of pearls are cultured (human-started). True natural pearls are auction-house rarities. No true synthetic exists. | "Majorica" or "shell pearls" are simulants, not synthetics. Cultured pearls are real pearls but not "natural" in the gemological sense. |

| Amber | Fossilized organic material. Its value is in its age, inclusions, and specific fossilization process. | Copals (young resin) and plastics are common simulants. Pressed amber (ambroid) is reconstructed from small pieces. | You can't "grow" a fossil. Any "lab amber" is imitation material like plastic or resin. |

| Painite (Historically) | Extreme rarity and complex chemistry (contains boron and zirconium). Was once called the world's rarest gem. | New deposits found, so rarity decreased. Synthesis was never pursued due to initial scarcity and complex makeup. | A great example of a gem that was "unmakeable" due to no commercial incentive. Now found in nature, still not synthesized. |

| Certain Colored Sapphires/Rubies (with specific inclusions) | It's not the mineral, but the scene inside. Unique inclusion scenes (silk, color zoning) that tell a geological story. | Labs can grow perfect corundum (sapphire/ruby). They cannot replicate the unique, desirable imperfections of a specific natural stone. | This is a key nuance. The gem species can be made, but the individual character of a prized natural stone cannot. |

Let me zoom in on jadeite for a second, because it's the king of this category. I remember a client bringing in a bracelet they bought online, convinced it was natural imperial jade because the listing said "lab-created" wasn't an option. It was a beautiful, deep green stone. Under the microscope? It was glass. The seller used a technical truth—you can't buy lab-created jadeite—to sell a complete fake. That's the level of confusion we're dealing with.

The GIA has extensive research on jadeite synthesis attempts, and their conclusion is clear: what's on the market as "synthetic jade" is almost always a simulant like dyed quartz, glass, or polymer composite.

Playing the Identification Game: How to Spot the Real Deal

So, you're interested in one of these natural-only gems. How do you not get taken for a ride? Forget the old wives' tales. The tooth test for amber? Useless. The "feel" of jade? Too subjective.

Your only real weapon is paperwork from a top-tier, independent gem lab. I'm talking about the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) or the American Gemological Laboratories (AGL). For high-value items, nothing else should be acceptable.

Here’s what to look for on those reports:

- For Jadeite: The report must explicitly say "jadeite jade" and list the treatment (if any, like polymer impregnation). Origin (like Myanmar) might be noted. If it's natural and untreated, that's where the premium lies.

- For Natural Pearls: The report will state "natural saltwater pearl." If it says "cultured pearl," that's a different (and still valuable) product. A GIA report for pearls often includes X-ray imagery showing the internal structure, which is a dead giveaway.

- For Amber: A proper report will confirm it's natural amber and may specify if it's tested for being copal (young resin) or if it has been treated (like heated for clarity).

One of the biggest mistakes I see collectors make is trusting a vendor's "in-house certificate." That's just a fancy sales receipt. Insist on independent verification. The fee for a lab report is the best insurance you can buy.

Your Questions Answered: The Practical Stuff

The landscape of gemstones is changing fast. But in the quiet corners of high-pressure geology and ancient biology, nature still holds a few secrets close. Understanding that not everything can or will be made in a lab helps us appreciate the true rarity and wonder of the stones that continue to defy our best technology. It's not just about what we can make, but about what the earth, against all odds, decided to make for itself.