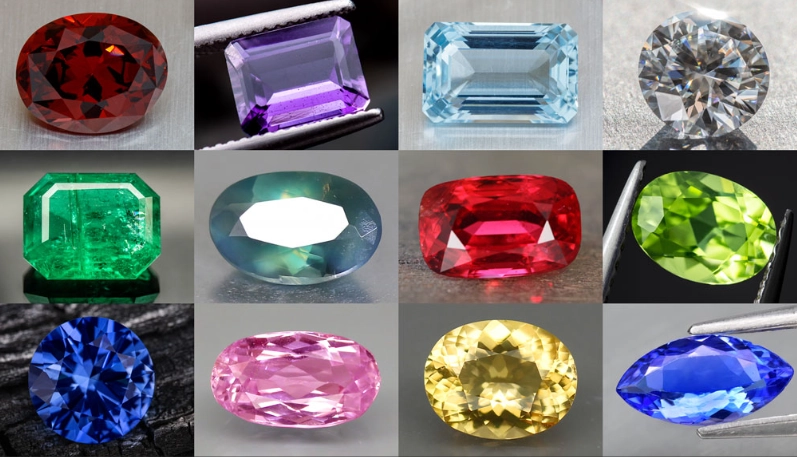

Let's cut to the chase. When people ask about the rarest birthstones, they're not just curious—they're hunting for the ultimate collector's item, the geological unicorn. It's not about what's expensive (diamonds can be pricey, but they're everywhere). True rarity is about stones so scarce that most jewelers have never held one, and your chances of finding a natural specimen in a shop are virtually zero. Based on factors like limited geographic sources, microscopic yields, and the sheer improbability of gem-quality formation, here are the five that truly deserve the title.

Your Quick Guide to the Rarest Five

- 1. Alexandrite (June): The Color-Changing Phantom

- 2. Red Beryl ("Bixbite"): The Utah Volcano's Red Secret

- 3. Painite: Once the World's Rarest Mineral

- 4. Black Opal (October): Lightning Ridge's Fiery Treasure

- 5. Demantoid Garnet (January): The Horsetail Firework

- Why Are These Birthstones So Rare?

- Finding and Buying: A Reality Check

1. Alexandrite (June): The Color-Changing Phantom

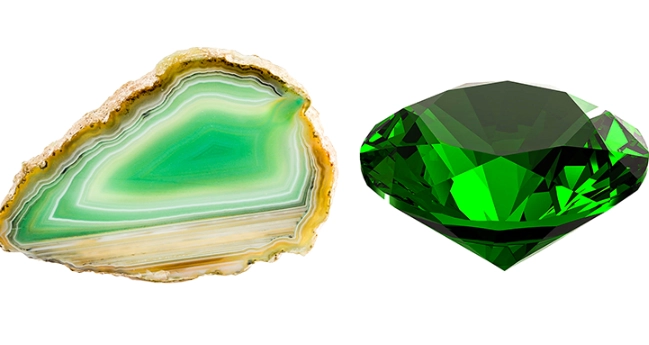

Rarity isn't just about how many exist—it's about how many exist with the magic. For alexandrite, the magic is its legendary color change: emerald green in daylight to raspberry red under incandescent light. This happens because of trace chromium, the same element that makes rubies red and emeralds green, but in a crystal structure that plays tricks with light.

The catch? The original Russian deposits from the 1830s, found in the Ural Mountains, are essentially exhausted. Stones from there are museum pieces. Newer sources in Brazil, Sri Lanka, and Africa produce alexandrite, but the color change is often less dramatic (greenish to purplish). A fine, strong-change Russian-style alexandrite over one carat? You're looking at a six or seven-figure gem.

2. Red Beryl ("Bixbite"): The Utah Volcano's Red Secret

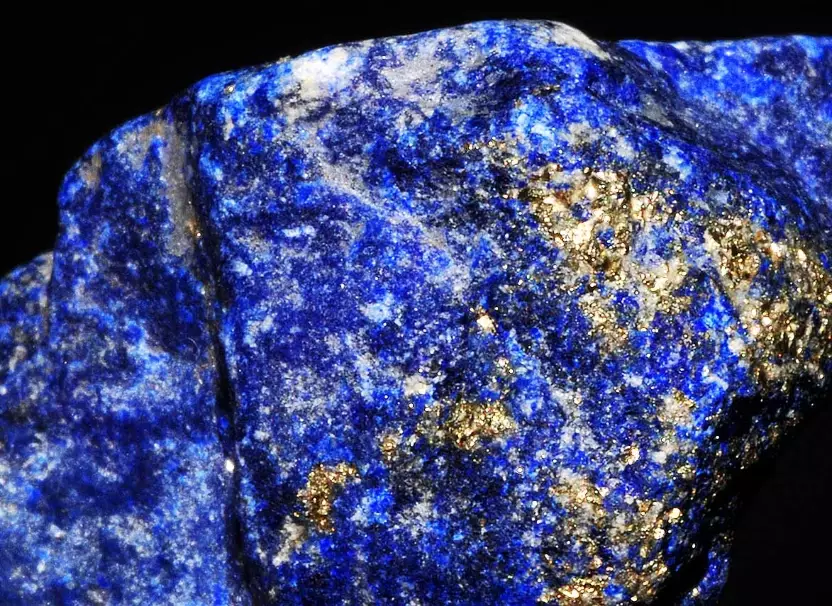

Forget emerald. If you want a truly rare green beryl, that's tough. But if you want a red beryl? You're asking for a geological miracle. Red beryl forms in a specific type of cooling lava where beryllium (common in emeralds) and manganese (which provides the red color) are forced together under unique conditions. This basically only happened consistently in one place: the Wah Wah Mountains of Utah, USA.

The yield is absurd. It's estimated that for every 150,000 gem-quality diamonds unearthed, one crystal of gem-quality red beryl is found. Most crystals are a few millimeters long. A one-carat faceted red beryl is considered large, and a two-carat stone is a landmark. You don't buy this by the carat; you buy it because you found one for sale at all.

3. Painite: Once the World's Rarest Mineral

Here's a stone that held the Guinness World Record for rarity. Discovered in the 1950s in Myanmar, only a couple of crystals were known for decades. The chemistry is bizarrely complex (calcium, zirconium, boron, aluminum, with trace chromium and vanadium). For years, museums had tiny fragments.

A new deposit was found in Myanmar in the early 2000s, producing more material. So, is it off the list? Not quite. While more "common" now, gem-quality facetable painite is still extraordinarily rare. The new material is often heavily included or opaque. A clean, well-cut painite over a carat retains its legendary status and price tag. It's a reminder that rarity can shift, but true gem-quality scarcity endures.

4. Black Opal (October): Lightning Ridge's Fiery Treasure

Opal itself isn't rare. But precious opal with play-of-color is. And the king of all opals is the black opal from Lightning Ridge, Australia. The "black" refers to the dark body tone (which can be dark blue, grey, or black) that makes the spectral colors blazingly vivid. It's not a different mineral; it's the pinnacle of opal formation.

Why is it here? Because the specific conditions at Lightning Ridge—an ancient inland sea bed with the right silica and the right seepage of acidic water—created this dark base color. Other places produce black opal, but none match the consistent, electric fire of Lightning Ridge material. Mining is brutal, small-scale, and largely luck-based. A top-grade black opal with a full spectrum of color (red being the rarest flash) on a solid black background commands prices per carat that rival fine sapphires and rubies.

5. Demantoid Garnet (January): The Horsetail Firework

Most people think garnets are cheap, red stones. Demantoid laughs at that notion. It's a vivid green garnet, part of the andradite family, with a dispersion (fire) that exceeds diamond. The classic source is the Ural Mountains of Russia (again), famous for one specific inclusion: radiating fibers of chrysotile asbestos called "horsetails."

Counterintuitively, in demantoid, these inclusions are often desired as proof of origin and can enhance the stone's beauty, making it look like it has a frozen golden firework inside. Clean, large demantoids without horsetails are actually rarer and can be worth more, but collectors love the classic look. New sources in Namibia and Madagascar produce beautiful material, often with less or no horsetails, but the Russian stones with their distinct golden threads remain the archetype of rarity and desire.

Why Are These Birthstones So Rare? The Geology of Scarcity

It's not an accident. Each of these stones is a prisoner of its own chemical recipe.

- Improbable Elemental Cocktails: Red beryl needs beryllium and manganese in lava. Alexandrite needs chromium in chrysoberyl without turning into something else. Painite's recipe is a periodic table scramble.

- The Gem-Quality Bottleneck: A mineral can exist, but being transparent, richly colored, and large enough to cut is another universe of luck. Most red beryl and painite is not gem-quality.

- Single, Depleted Sources: The original, best material for alexandrite, demantoid, and black opal came from one primary, now-tired location. Second sources exist but often don't match the classic quality.

This is what separates them from a diamond. Diamonds are concentrated in mines that yield thousands of carats. A commercial alexandrite mine might yield a handful of facetable material per year.

Finding and Buying: A Reality Check

So you want one? Let's be practical.

You will not find these at your local jewelry chain. Your path is through:

- Specialist Gem Dealers: Dealers who cater to collectors and high-end designers. They often have waitlists for stones like red beryl.

- Custom Cutters: Many buy rough directly from small-scale miners and cut to order. This is a great way to get a unique stone, but you need trust and patience.

- Auction Houses: Major auctions like Christie's or Sotheby's often feature exceptional specimens of these rarities.

Always, always get an independent laboratory report from GIA, AGL, or Gübelin for any significant purchase. For these stones, provenance and verification are everything.

Your Rare Birthstone Questions Answered

Is a diamond considered one of the rarest birthstones?

No, surprisingly, diamond (April's birthstone) is not among the rarest. While high-quality diamonds are valuable, they are mined in significant commercial quantities globally. Rarity is about limited geological occurrence and tiny yields, which describes gems like alexandrite or red beryl far better than diamond. The diamond market is about controlled supply, not true geological scarcity.

Can I find the rarest birthstones in regular jewelry stores?

Almost never. You won't find natural alexandrite, red beryl, or painite sitting next to sapphires and emeralds at a mall jeweler. These stones are primarily handled by specialist dealers, at high-end auctions, or through custom gem cutters who source directly from miners. For most people, seeing one requires a trip to a major natural history museum like the Smithsonian.

Why is synthetic or lab-created not a good alternative for these rare stones?

It depends on your goal. Lab-created versions exist for some, like alexandrite, and are fine for enjoying the color. But they completely miss the point of the rarity. The astronomical value and collector fascination are tied to the near-impossible natural geological conditions that created the original stone. A synthetic has none of that history, scarcity, or investment potential. It's a costume piece versus a natural wonder.

What's the most important factor making a birthstone rare?

A combination of two things: an extremely specific and uncommon geological recipe needed to form the mineral, and then the vanishingly small chance that the resulting crystals are of gem quality—meaning they have the right color, clarity, and size to be cut. A mineral can be rare (like painite was), but gem-quality specimens of that mineral can be virtually non-existent, which is the case for several on this list.