Quick Guide

- Shifting Your Mindset: What Are You Actually Looking At?

- The First Clue: Visual Inspection and Simple Tests

- Digging Deeper: Key Physical Properties

- The Role of Light and Optics

- Putting It All Together: A Practical Identification Workflow

- Common Gemstones in the Rough: A Quick-Reference Table

- When and How to Get a Professional Opinion

- Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

- Wrapping Up: The Journey is the Reward

Let's be honest. There's a special kind of magic in picking up a dull, dirty rock and wondering, just for a second, if you're holding something precious. I remember my first time out in a known quartz field. Everything glittered in the sun, and I was convinced I'd found a diamond mine. Of course, it was just common quartz with great cleavage planes catching the light. A bit disappointing, but it started a lifelong curiosity. That curiosity is what drives most of us to learn how to identify gemstones in the rough. It's not about getting rich quick—most of the time, you won't. It's about the thrill of the hunt and understanding the silent language of the earth.

Maybe you've brought home a souvenir from a hike, or you're sifting through gravel at a pay-to-dig site. You have this lump in your hand, and the question nags at you: What is this? Is it just a pretty rock, or could it be a gem in its raw, unpolished state? The process of learning how to identify gemstones in the rough is part detective work, part science experiment, and a whole lot of patient observation. It's a skill that demystifies the ground beneath your feet.

Shifting Your Mindset: What Are You Actually Looking At?

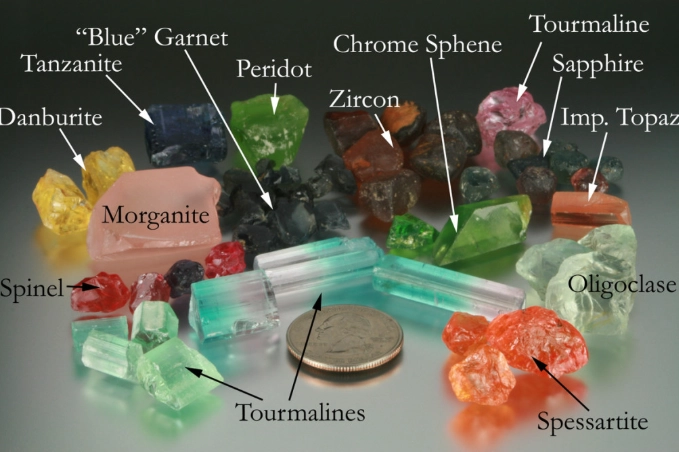

The biggest hurdle for beginners isn't the lack of tools; it's the lack of context. A cut and polished gem in a jewelry store looks nothing like its natural form. A rough sapphire looks like a worn, glassy pebble. An uncut emerald often looks like a piece of green, foggy ice. The glamour is added by the lapidary. Your first job is to forget the glitter and learn to see the raw material.

You're not just looking for "pretty." You're looking for specific combinations of physical properties that point to a specific mineral family. A gemstone is, at its core, a mineral that is beautiful, durable, and rare enough to be used for adornment. So, when you're figuring out how to identify gemstones in the rough, you're essentially performing basic mineral identification with a focus on the candidates that have gem potential.

It's more about elimination than instant recognition.

Start by asking yourself some basic questions about your mystery rock. Is it metallic or non-metallic in luster? Does it feel heavy for its size? Does it have a crystal shape, even if it's broken? Jotting down these initial observations is more helpful than you think. I keep a small notebook in my field bag because memory can play tricks, especially after a long day in the sun.

The First Clue: Visual Inspection and Simple Tests

Before you reach for any fancy gear, use the tools you were born with: your eyes and your hands. This initial screening can narrow down the possibilities dramatically.

Color and Luster: The First Glance

Color is the most obvious feature, but also the most deceptive. Impurities can dye common minerals in surprising ways. That said, color can point you in a general direction.

- Blues/Blue-Greens: Point towards aquamarine/beryl, turquoise, chrysocolla, or possibly azurite.

- Greens: Could be peridot (olivine), various forms of jade (nephrite/jadeite), malachite, or of course, emerald (which is just green beryl).

- Reds/Pinks: Garnet (almandine, rhodolite), ruby (red corundum), spinel, or rhodonite.

- Purples: Almost always whispers "amethyst" (purple quartz), but could be fluorite or lepidolite.

- Yellows/Oranges: Citrine (yellow quartz), topaz, spessartine garnet, or amber (which is organic, not a mineral).

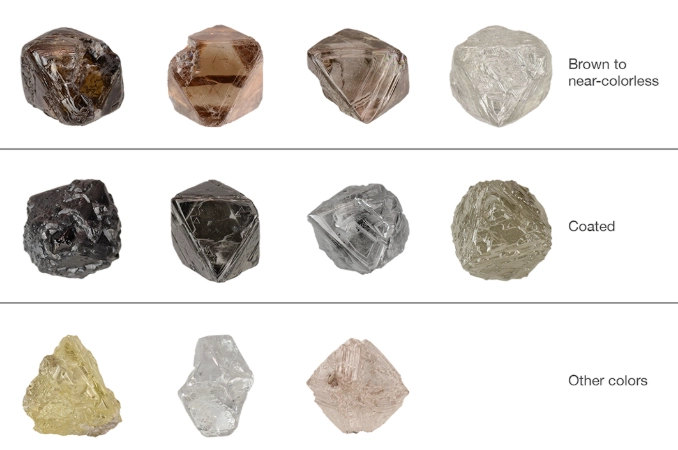

Luster is how light interacts with the surface. Is it glassy (vitreous) like quartz? Metallic like pyrite? Waxy like turquoise or jade? Pearly like some cleavage faces? Silky like tiger's eye? Getting the luster right is a huge first step in learning how to identify gemstones in the rough. A diamond in the rough, for instance, often has a greasy luster, not the brilliant sparkle you'd expect.

Crystal Form and Habit: Nature's Signature

Even when broken, many rough gems retain hints of their crystal structure. This is a massive clue. Does it have flat, geometric faces? Are the faces smooth or striated? Is it a perfect six-sided prism (like quartz often is)? Or is it a bunch of tiny, interlocking cubes (like garnet can be)?

Look up common crystal systems: cubic (diamond, garnet, fluorite), hexagonal (beryl, corundum, quartz), tetragonal (zircon), and orthorhombic (topaz, peridot). You don't need to memorize them all, but having a basic chart or app reference in the field helps immensely. I can't tell you how many times I've mistaken a broken quartz crystal for something more exotic because I didn't check the angles of the faces.

Hardness: The Scratch Test (The King of Tests)

This is arguably the most important practical test for identifying gemstones in the rough. The Mohs scale of mineral hardness ranks minerals from 1 (talc, very soft) to 10 (diamond). The principle is simple: a mineral of a higher number can scratch a mineral of a lower number.

You don't need a full set of picks. Get yourself a few key items:

- Fingernail (Hardness ~2.5): Can you scratch it? If yes, it's very soft (like gypsum or talc).

- A copper penny (Hardness ~3.5): If your fingernail doesn't scratch it, but a penny does, it's in the 3-3.5 range (e.g., calcite).

- A pocket knife or steel nail (Hardness ~5.5): This is a major divider. If the steel scratches it, the mineral is below 5.5. If it does not scratch it, the mineral is 5.5 or above. Most common gemstones (quartz at 7, topaz at 8, corundum at 9) are above 5.5.

- A piece of quartz (Hardness 7): If your specimen can scratch glass (which is around 5.5), it's at least 6. If it can scratch your quartz piece, it's 7 or higher. This is a great way to separate quartz from topaz or corundum.

This test alone can save you from embarrassing mistakes. I once saw someone at a gem show trying to sell "rough emerald" that was easily scratched by a knife. Emerald (beryl) has a hardness of 7.5-8. It was almost certainly green glass or something like fluorite.

Digging Deeper: Key Physical Properties

Once you've done your visual and hardness checks, you can move on to other distinctive properties. These tests require a bit more attention but are still doable at home or in the field.

Streak: The Color of the Powder

This is a fantastic test for minerals with a metallic luster or those where the external color is misleading. The streak is the color of the mineral's powder. You find it by rubbing the mineral against an unglazed porcelain tile, called a streak plate (you can buy these cheaply).

The crazy thing? The streak color can be completely different from the bulk color. Hematite, which looks dark gray or black, has a distinctive cherry-red or reddish-brown streak. Pyrite (Fool's Gold) is brassy yellow but gives a greenish-black streak. This test is a dead giveaway for those minerals. For harder gemstones like quartz or corundum, they are harder than the streak plate, so they won't leave a streak. That's data too!

Specific Gravity (Heft): Feeling the Density

This is the "heft" test. Some minerals are just denser than others. Pyrite feels much heavier than a similarly sized piece of quartz. A piece of hematite feels like a lead weight. This subjective feel comes with practice. Pick up a known piece of quartz. Remember how it feels for its size. Now compare your unknown specimen. Does it feel surprisingly heavy (high specific gravity, like garnet, corundum, or topaz) or surprisingly light (low specific gravity, like opal or amber)?

It's not precise, but your hands are smarter than you think.

Cleavage and Fracture: How It Breaks

This refers to the pattern in which a mineral breaks. Cleavage is a clean break along planes of atomic weakness, creating flat, shiny surfaces. Mica is the classic example—it peels into perfect sheets. Topaz has one perfect cleavage direction, which is why cutters have to be very careful with it. Fracture is an irregular break. Conchoidal fracture (smooth, curved surfaces like broken glass) is very characteristic of quartz and opal.

Examining a broken edge of your rough material can tell you a lot. Seeing that conchoidal fracture is a strong indicator you're dealing with a glassy material like quartz or flint, not something with cleavage like feldspar.

The Role of Light and Optics

Light behaves in strange and wonderful ways inside crystals. Two simple optical tests can provide powerful clues.

Dichroism (Pleochroism): Two Colors in One Stone

Many gemstones appear to show different colors or shades when viewed from different directions. This is called pleochroism (dichroism for two colors). It's a hallmark of non-cubic crystals. A simple, inexpensive tool called a dichroscope helps see this, but you can sometimes see it with the naked eye by rotating the stone against a white background in good light.

Iolite is famous for this—it can look violet-blue, gray, and pale yellow from different angles. Tanzanite is strongly trichroic. Seeing this effect immediately rules out a huge number of common look-alikes like glass, which is isotropic and shows no color change.

Refractive Index and the "Sparkle"

While measuring Refractive Index (RI) precisely requires a refractometer (a key tool for serious identifiers), you can get a rough sense. Minerals with a high RI (like diamond, zircon, garnet) tend to have a more brilliant, "sharp" luster even in the rough, because they bend light more. Compare the surface shine of a piece of quartz (RI ~1.55) to a piece of zircon (RI ~1.95). The zircon just looks "sharper" and brighter. It's a subtle cue, but with practice, you'll start to notice.

Putting It All Together: A Practical Identification Workflow

So you have a mystery rock. Here's a logical sequence for how to identify gemstones in the rough, step-by-step. Don't skip steps.

- Observe & Record: Note color, luster, crystal shape, transparency. Where did you find it (geographic location can be a huge clue)?

- Test Hardness: Use your fingernail, penny, and knife/steel nail. This gives you your first solid number.

- Check Streak: If the mineral is soft enough, see what color powder it makes.

- Assess Cleavage/Fracture: Look at any broken edges.

- Feel the Heft: Compare its weight to a known mineral like quartz.

- Do Simple Optical Checks: Look for color change (pleochroism) and note the character of the luster.

- Consult References: Use your notes to look up possibilities in a field guide or reputable online database.

This process is iterative. You might go back and re-check hardness after considering a new possibility. The goal isn't always a definitive ID on the spot—it's to narrow it down to a few strong candidates that you can then research further or take to an expert.

Common Gemstones in the Rough: A Quick-Reference Table

Here’s a look at some of the most frequently encountered (or sought-after) gem materials and their key rough characteristics. This table is a starting point, not a definitive guide, as variations are common.

| Gemstone (Mineral) | Typical Rough Appearance | Hardness (Mohs) | Key Identifying Features | Common Look-Alikes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quartz (Amethyst, Citrine, Smoky) | Six-sided prismatic crystals, often terminated. Conchoidal fracture. Can be massive. | 7 | Glassy luster. Hardness 7 (scratches glass easily). No cleavage. | Calcite (softer, H=3), Glass (conchoidal fracture but often contains bubbles). |

| Beryl (Aquamarine, Emerald) | Long, hexagonal prisms. Often worn into pebbles in alluvial deposits. | 7.5-8 | Harder than quartz. Hexagonal crystal shape is a giveaway. Often somewhat included. | Green tourmaline (different crystal form, more striated), Apatite (much softer, H=5). |

| Corundum (Ruby, Sapphire) | Barrel-shaped, hexagonal crystals. Often waterworn into rounded, pitted pebbles ("alluvial rough"). | 9 | Extremely hard (scratches almost everything else). Greasy or adamantine luster. Often shows color zoning. | Garnet (different crystal form, often isotropic), Spinel (softer, H=8, cubic crystals). |

| Garnet (Almandine, etc.) | Often found as rounded, dodecahedral (12-sided) or trapezohedral crystals. Can be massive. | 6.5-7.5 | High specific gravity (feels heavy). Isotropic (no double refraction). | Some tourmaline, Spinel. |

| Topaz | Prismatic crystals with vertical striations. Often has a basal cleavage plane. | 8 | Hardness 8. One perfect cleavage. Can feel heavy for its size. | Quartz (softer, no cleavage), Citrine quartz (often confused). |

| Tourmaline | Long, striated prisms with triangular cross-sections. Often color-zoned (watermelon tourmaline). | 7-7.5 | Unique crystal habit. Strong pleochroism. Pyroelectric (can attract dust when heated/cooled). |

When and How to Get a Professional Opinion

You've done all your tests, you're 80% sure, but there's that lingering doubt. That's normal. Here's when you should consider taking your find to a professional:

- If you suspect it might be something of significant value (like a potential diamond, ruby, or emerald).

- If your tests give contradictory results.

- If you simply want a definitive, certified identification for your collection.

Look for a Graduate Gemologist (GG) from the Gemological Institute of America (GIA) or a similarly qualified gemologist/appraiser. They have access to advanced tools like refractometers, spectroscopes, and microscopes that can provide conclusive evidence. Local rock and mineral clubs are also fantastic resources—the collective experience there is immense and often freely shared. The Mineralogical Society of America has great resources for finding clubs and reliable information.

Avoid taking it to a random jeweler who only deals in finished pieces. They may not have the expertise or equipment for raw identification.

The final, authoritative step in learning how to identify gemstones in the rough often involves acknowledging when you need an expert's eyes and tools. There's no shame in it; it's part of the learning process.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Sometimes. Many minerals fluoresce under ultraviolet light (longwave or shortwave). For example, some rubies fluoresce strong red, some scheelite (a tungsten ore) fluoresces bright blue, and some opals can show a greenish glow. It's a helpful supplementary test, but it's not definitive. Many non-gem minerals also fluoresce, and many gemstones don't. Don't buy a cheap "gem detecting" UV light that makes wild claims—they're often gimmicks. A real UV lamp is a specific tool for a specific clue.

Wishful thinking, followed by misapplying the hardness test. We all want to find the motherlode. This leads to ignoring contradictory evidence (like that "emerald" being soft). The other big one is not doing the scratch test correctly—scratching the tester with the unknown mineral, or confusing powder residue for a true scratch. Go slow, be methodical, and be brutally honest with your observations.

Legally, first and foremost! Always get permission if you're on private land. Public lands have specific rules (check with the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) or relevant forest service). The best places are often known dig sites, old mine tailings (with extreme caution), and stream beds (alluvial deposits). Geography is destiny in rockhounding. You won't find Oregon sunstone in Florida. Research the geologic history of your area.

There are several, and their accuracy is... mixed. They can sometimes give you a plausible suggestion based on color and texture, which can be a starting point for your own investigation. However, they cannot perform physical tests like hardness or streak. Never rely solely on an app photo ID, especially for anything you think might be valuable. Use them as a digital field guide companion, not an oracle.

Wrapping Up: The Journey is the Reward

Learning how to identify gemstones in the rough is a journey that never really ends. There's always a new mineral to learn about, a new test to understand, a new location to explore. The real treasure isn't just the occasional flash of color in a rock; it's the knowledge you build, the connection to the natural world you forge, and the quiet satisfaction of looking at a stone and finally understanding its story.

Start with the basics. Master the hardness test. Get your eyes used to seeing luster and crystal form. Handle as many identified specimens as you can—this "library" in your hands is irreplaceable. Join a club. Make mistakes (I've got a box of "interesting rocks" that turned out to be slag glass). Ask questions.

The earth is full of hidden wonders. Now you have a few more keys to start unlocking them.